Would you like to know who you are? Then it is essential to know what is of real value to you. One way of finding that out is by asking the question, “What would I be willing to give up for something that I claim is important to me? What would I be willing to sacrifice for love, or great wealth, or power, or honor, or for my child’s well-being?”

What we are willing to sacrifice defines us, both as individuals and as a society. But first, let’s look at what the word sacrifice means:

The on-line Merriam-Webster’s dictionary gives the following definition of the noun sacrifice:

1 : an act of offering to a deity something precious; especially : the killing of a victim on an altar

2 : something offered in sacrifice

3 a : destruction or surrender of something for the sake of something else b : something given up or lost <the sacrifices made by parents>

4 : loss <goods sold at a sacrifice>

Thus sacrifice involves loss and giving something up.

In primitive societies, it often included murder.

Human sacrifice was intended most often to appease a God, win the God’s favor, or avoid the God’s wrath. Igor Stravinsky wrote a famous ballet about this, The Rite of Spring.

More recent depictions of this sort of behavior have included Friedrich Dürrenmatt’s 1956 novel, The Visit. In this story a wealthy woman (Claire Zachanassian) returns for a visit to her home town, a place that has fallen on hard times. She departed in disgrace many years before when she was impregnated by her young lover. This person denied the charge of paternity and bribed two people to support his case by claiming that they had been intimate with her. Shamed by the townsfolk, Claire eventually turned to prostitution.

Her return home is noteworthy for a “proposition” she has for the town where her former lover continues to live as a respected businessman. She will bequeath an enormous sum to the hamlet if it will do one simple thing: put to death the man who caused her disgrace. In effect, the book asks the question of what this woman is willing to sacrifice for revenge (her money, her morality) and what the town’s people are willing to give up for money. The movie of the same name starred Ingrid Bergman and Anthony Quinn.

More recently, a very different sort of sacrifice is depicted in a 1967 episode of the original Star Trek TV series, The City on the Edge of Forever. While in an irrational state, the ship’s physician enters a time portal on an alien planet, one that takes him back to 20th century USA in the midst of the Great Depression.

At the instant that this happens, the Enterprise starship disappears from its orbit of the world on which the time portal exists. Captain Kirk and Mr. Spock, already on the planet in pursuit of Dr. McCoy, recognize that he must have altered history in such a way as to result in a universe in which their space vehicle never existed. Kirk and Spock therefore enter the time portal themselves at a moment in history slightly before they believe that McCoy reached 20th century earth, in order to prevent whatever action he took that changed subsequent events.

While back in time, Kirk and Spock meet a social worker named Edith Keeler, who runs a soup kitchen for the down-and-out victims of the Depression. Soon, Mr. Spock uses his technological prowess to discover that Dr. McCoy will eventually have something to do with Edith Keeler herself.

In one possible historical thread, Spock finds a newspaper obituary for her. In another, however, he discovers that she will lead a pacifist movement that delays the USA’s entry into World War II, resulting in Hitler’s victory and the very alteration of events that prevented creation of the star fleet of which the Enterprise starship is a part. Thus, in order to create the more benign future known to the three officers, Edith Keeler must die.

There is only one complication. Captain Kirk and Edith Keeler (played by Joan Collins) have fallen in love.

The climatic moment comes when Dr. McCoy and Captain Kirk see each other across the street for the first time on 20th century earth. As they rush to reunite, Edith Keeler (on a date with Kirk), attempts to cross the street to join them, heedless of the fact that a fast-moving truck is headed toward her. The doctor attempts to rescue Kirk’s love, but is restrained by Kirk from doing so. Edith Keeler is killed.

The heartbreak is heightened by the incredulous McCoy’s indictment of his captain and friend: “I could have saved her…do you know what you just did?.” Unable to speak, Kirk turns away while Mr. Spock says quietly, “He knows, Doctor. He knows.” Thus, Kirk has sacrificed Edith Keeler’s life and his own happiness, to prevent her from actions that would have led to world enslavement by the Third Reich.

—

I have always been troubled that two of the most important biblical stories involve human sacrifice. The tale of Abraham and Isaac finds the former, the founder of the Jewish faith and monotheism, asked to sacrifice his son Isaac in order to prove his devotion to God. As he prepares to do this, an angel appears and stays his hand. A lamb is slaughtered instead. Rembrandt depicted this beautifully in the painting reproduced above.

Remember now, that I’m a psychologist. I cannot look at this painting without wondering what the child Isaac might be thinking and feeling in the aftermath of this moment. How will his relationship with his father be changed? Might there have been other possible ways of testing Abraham without permanently scarring his son?

The foundation story of Christianity poses a virtually identical dilemma, with the sacrifice of Jesus to pay for the sins of humanity. I fear that we are so used to abstracted representations of these events, that we have become inoculated against the trauma depicted by them and the human, societal, and theological implications of such horrors, reportedly authorized by God.

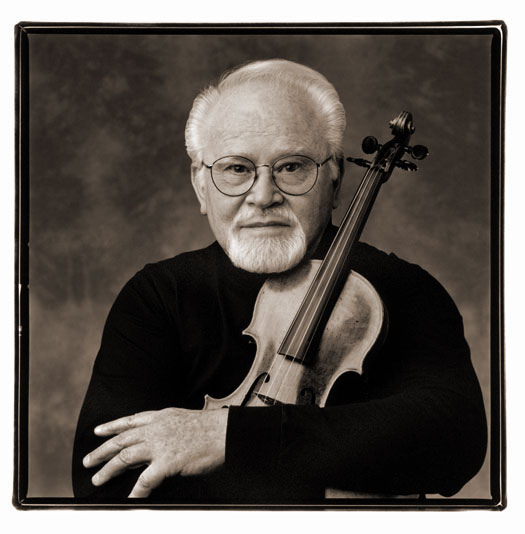

Of course, most of our sacrifices are much less dramatic. Do we give up eating what we might want in order to be fit and live a longer and healthier life? Do we brush off the attractive member of the opposite sex who “comes on” to us, in order to maintain our marital fidelity, avoid injuring our spouse and children, and keep whole our integrity? Do we sacrifice time having fun or attempting to climb the career ladder in order to go to our child’s boring orchestral recital and enduring hours of “Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star” played by tiny violinists, all of whom are out of tune?

I’m sure you can imagine many more such choices and sacrifices of your own.

We make decisions, all of us, about the question of national sacrifices too. Jobs vs. clean air, tax cuts vs. social services, giving to charity vs. keeping the money for ourselves, liberty vs. the promise of security, and most poignant of all, the decision of when war is necessary despite the sacrifice of the unlived lives of our young adult children.

Just as an exercise, you might want to make a list of all those things you spend time on that are inessential, all the things that you could live without if it came to something really important.

Or, still another exercise: if you could only take 10 things or 10 people with you to a desert island, who or what would they be and who or what would you leave behind? And what cause would be great enough for you to agree to go to a desert island in the first place?

Who are we as a nation? Who are you as a person?

We might know more about our country and ourselves if we first ask what we are willing (and unwilling) to sacrifice.

—

The top image is the Sacrifice of Isaac by Rembrandt. The second picture, taken by Michael Gäbler, is of Adi Holzer’s hand colored etching Abrahams Opfer from 1997. Finally, Caravaggio’s version of the same scene Die Opferung Isaaks from 1594-96, sourced via the Yorck Project. All of the above come from Wikimedia Commons.