Last week, the Chicago Symphony’s former 82-year-old conductor had reason to be unhappy. By contrast, his successor and future occupier of that throne, a tall, energetic, and ambitious 28-year-old, was feeling on top of the world.

The latter, Klaus Mäkelä of Finland, failed to mention the most recent CSO Music Director in interviews celebrating his own designation as the ensemble’s leader beginning in 2027. Ricardo Muti, the former head of the glorious band, is the fellow whose name was absent.

Here is an excerpt from Mäkelä’s April 5th interview with WBEZ Radio’s Courtney Kueppers. The young man offers a telling description of the sound of the Chicago musicians and two of those who created it:

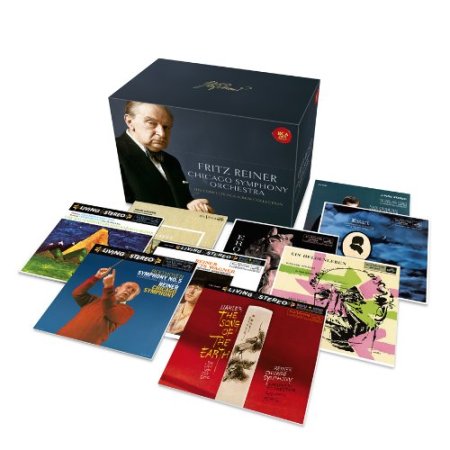

It’s an amazing sound. Its brilliance, its shine, its strength, its everything. And it’s really touching to hear. I was thinking about yesterday, when I started rehearsing, I listened to all the recordings — I love the old recordings and all the recordings of the past — and there were some moments when I thought: Oh my god, this sounds exactly like a Fritz Reiner recording [Reiner was CSO’s maestro in the 1950s] or a [Georg] Solti [the Chicago orchestra’s longtime music director] … And I think that’s incredible that they’ve managed to preserve it. And of course, my job is to also further develop it, but also preserve it. And I think it’s so wonderful because in today’s world, orchestras start sounding the same. And we need voices which are really original.

Hmm. Why might Mäkelä have neglected Muti, now the CSO’s Conductor Emeritus? No doubt, Maestro Muti believes he did more than “preserve” the orchestra’s qualities in his 13 years as top man.

But Mäkelä associated himself with the two most significant conductors in the Windy City since the middle of the last century. One gathers that he expects to fill their shoes. As Daniel Burnham, the architect who designed the CSO’s Orchestra Hall, wrote:

Make no little plans. They have no magic to stir men’s blood and probably will not themselves be realized.

Reiner and Solti would have agreed. They did more than “preservation” of the status quo. They made “no little plans.”

Fritz Reiner rebuilt a CSO in recovery from everything that had happened in Burnham’s building during the preceding 11 years.

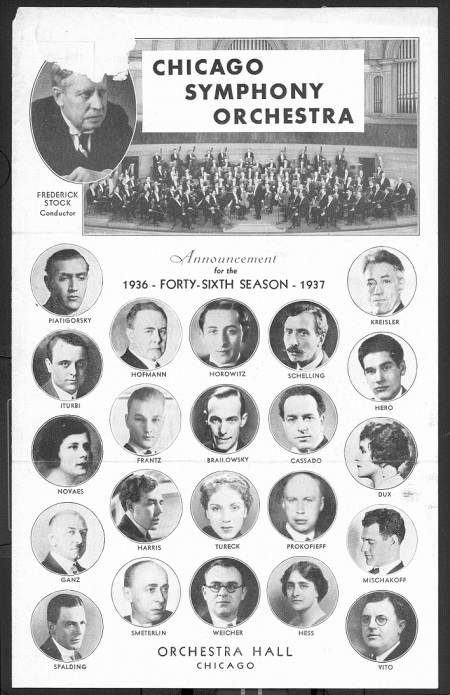

“Papa” Frederick Stock, their leader since 1905, died in late 1942. He was followed to the podium by Desire Defauw, who stayed for a less-than-stellar four-year tenure. World War II complicated the Belgian’s time, leaving him with 11 new players in his first season.

Artur Rodzinski lasted only a season (1947-48), and the 36-year-old Rafael Kubelik just three (1950-53). Fritz Reiner’s arrival at the end of 1953 raised the CSO on all levels, not least their long-playing records, which remain perhaps the most consistently fine group of discs in its history.

Amsterdam’s Royal Concertgebouw

Georg Solti’s contribution was different. A Hungarian like Reiner, Solti inherited many of the same players who performed with Reiner before Solti began as Music Director in 1969. The group included several fine personnel additions made by Jean Martinon, Reiner’s immediate successor, including Principal Horn Dale Clevenger.

Even so, the CSO had toured little domestically and never outside the USA. Solti made sure his new orchestra crossed the ocean. International fame and a flood of records followed, as did endless tours in the United States and abroad.

Klaus Mäkelä (K.M.) is in the habit of commending big, transformative names. Upon the news of becoming the future Chief Conductor of the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra of Amsterdam, he told Principal Double Bass Dominic Seldis of his admiration for Willem Mengelberg’s recorded legacy. The man K.M. named put that renowned ensemble on the map and led the first festival of Gustav Mahler’s complete Symphonies in 1920.

Mengelberg last conducted the Dutchmen in the 1940s. Mäkelä mentioned no one who served after that.

It is easy to conclude that Chicago’s youngest-ever Music Director wants to change an orchestra that must adapt to survive in the post-Covid world. His charm seems to belie an extraordinary self-confidence.

The job is enormous, and he knows he must replace 15 players out of the gate.

Who might Klaus Mäkelä have named if he’d been appointed to the Boston Symphony? Serge Koussevitzky, no doubt. But that conductor’s mark involved more than insisting on a ravishing orchestral tonality and realizing his interpretive genius in concert and on disc.

The BSO leader commissioned countless works and steadfastly championed them, including those of American composers. His fingerprints are also on Ravel’s orchestral transcription of Pictures at an Exhibition and Bartok’s Concerto for Orchestra.

In 1942, he established the Koussevitzky Music Foundation, which continues to support living composers. Moreover, Koussevitzky fashioned the New York Philharmonic’s summer concerts in the Berkshires into an annual warm-weather festival of the Boston Symphony at Tanglewood, focused on performance and the mentorship of young musicians.

Serge Koussevitzky

Successful conductors each possess a potent ego. One cannot stand before soloist-quality musicians of experience and intelligence without it. The players must be convinced you are worth their time, though they will carry you even if you aren’t. Everything suggests Mäkelä has the ego and technique to do the job.

The three conductors named by Mäkelä, as well as Koussevitzky, had that and more: a visionary quality that would take the men and women sitting before them somewhere beyond the next performance.

As Seldis noted in the Concertgebouw interview, Mäkelä’s new “office” — the glowing concert hall in which he will perform in Amsterdam — has 26 red-carpeted steps leading not far from the organ pipes down to the stage — a harrowing trip for some.

One can only hope that the steep descent he will walk signals nothing ominous about the talented baton-smith’s future. Two storied orchestras expect every bit of his capacity beginning in 2027.

My suggestion? As Former U.S. President Teddy Roosevelt said:

Speak softly and carry a big stick.

For now, a Burnham-like “plan” will have to wait.