The sense of being trapped may be a universal experience. Think of the small child who tries to wrestle out of his parent’s protective arms. The teen who hates curfew. The high school grad who can’t wait to leave home.

Other examples come to mind:

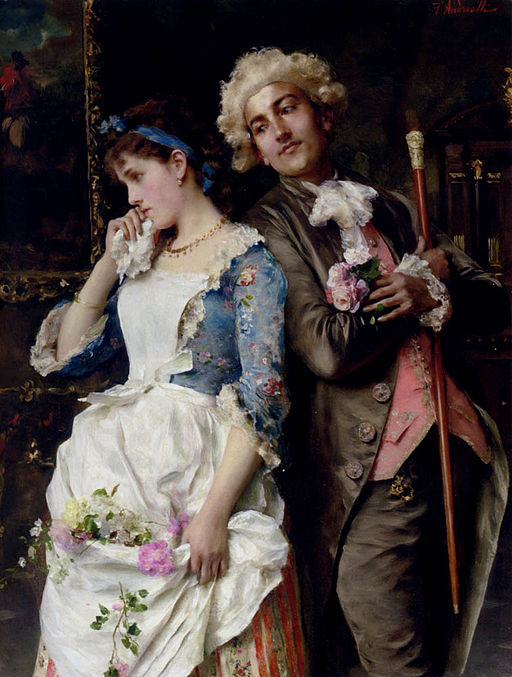

- The suffocating boyfriend from whom you must free yourself.

- The hated boss.

- The stifling career.

- The moribund marriage.

- A restrictive religion and its too many rules.

Why are we so offended by the stickiness of things, of being like a fly on flypaper? Why do fences shout “Jump”? What is it about walls that beg us to climb, even as recreation?

- Our ancient ancestors, the hunters and gatherers, needed to keep moving to find food and shelter. They profited by sensing and staying away from those animals and humans who menaced them. We inherited their survival tendencies. The complacent and trusting souls who acted otherwise and perished didn’t pass on their genes.

- The instinctive man inside of us habituates quickly: he gets used to things, becomes restless, gets bored. Dissatisfaction is built into our nature, the better to thrive and survive. Were we satisfied by a single meal, with no recurring hunger, we’d starve. If sex so “blissed-out” cave-dwellers after one or two couplings, you and I would not exist.

- The passage of time creates urgency. We don’t lead infinite lives. Want to be an Olympic star? Don’t wait until 30 to start practicing. The desire for love, too, means you must dive into the swim while your sparkle still can catch the eye of another aquatic creature.

The grass always being greener, where to? When? The five-year-old doesn’t run away because he can’t make a life on his own. The abused spouse with the ground-to-bits self-image holds her hopeless spot for fear worse awaits her elsewhere. The dissatisfied employee stays put in an economic depression. We all know out-of-love couples who remain married for the children, the worry of being vilified by co-religionists, and the thought of owning one dollar, where they used to count two.

We sometimes stay when we should escape and leave when we should hesitate. I’ve done both. How do you tell whether flight is best or portends even worse? A few things to consider:

- Nobel Prize winning psychologist Daniel Kahneman states, “It is only a slight exaggeration to say that happiness is the experience of spending time with people you love and who love you.”

- Psychologists remind us that experiences, not things, have more lasting value internally and are more positively remembered than buying one more material object.

- We cannot escape ourselves entirely. One’s innate temperament makes a significant contribution to happiness.

- What we choose to focus on and whether we set impossible goals also factor into our sense of satisfaction. These are within our control. The long-term practice of mindfulness meditation has been associated with happiness, as well.

- Research suggests Midwesterners who believe life will be better in California simply because of the weather tend to discover fair weather, like almost everything else, gets absorbed into the background. Not only climate, of course, is subject to habituation: think money, a new car, and today’s Christmas toy – the new delight turned stale; closeted before the weather warms. In the absence of other factors that might sustain a sense of well-being, we return to our set point, a basic and more or less enduring emotional state.

- A richer neighbor will always be a happiness-wrecker if $$ are the measure you crave. Above $75,000 per year, your moment-to-moment, experienced well-being doesn’t improve much.

- On the other hand, more money does tend to increase life satisfaction: your opinion of your life when you stop and think about it. And, up to about $75,000 yearly income, moment-to-moment happiness does increase.

- Ask yourself what is your default tendency. If you tend to change jobs quickly, for example, then the next question becomes, how is that working? If you are prone to stasis when dissatisfied, the same question must be answered.

- Are other lives involved in your decision? Maybe moving to a new house is best for you, but will it work for the spouse and kids?

- Try to predict how you will feel about your choice in five months or five years. We tend to be poor at “affective forecasting,” the ability to gauge the emotional consequences of our actions. Still, an attempt is required.

- A 2017 paper by Blanchflower and Oswald suggests we reach a low point to our happiness in midlife (around the early 50s). Thereafter, in general, we rebound – major life change or not.

- You will do better to know where you are going, than just the situation from which you flee.

- Those prone to anxiety and worry tend to exaggerate the danger of taking a risk. Judgment is questionable when angry. If you can, wait for a cool moment to make a decision.

- Who are you? What are your values? How do these translate into life as it is lived?

- Is there more than one way to achieve the result you want?

- You might ask yourself whether your internal life requires attention. The externals – other people, your job, your living conditions – are less in your control.

- If you expect utter and permanent transformation following your leap from a stuck place – well – you could be expecting too much. Remember, though, nothing in life is permanent and one can do worse than reach for the beguiling flowers still in bloom.

One last thought: we get no free lunch. Staying and going – except in extreme circumstances where life depends on it – each have a cost. Sometimes the decision is easy, often we struggle. Some doors remain open a while, others close with a rush. None of us get this right every time. Indeed, even knowing whether there is a “right” road can be challenging, since we only know with certainty the chosen path, while the other avenue lives in an idealized state within our imagination.

We’ve all read stories about the courage of people real or imagined, and the fixedness and quiet desperation of others. Those lives may provide guidance, but making choices presents a challenge unless you are an inveterate risk-taker or so frozen in place that no heat wave can de-ice and free you.

We each have only this one life. Try not to die with too many regrets.

—

The top image is the Vatican Museum Staircase as photographed by Andreas Tille. Next is James Jowers’s L.E. Side. These were sourced from Wikimedia Commons. Finally comes a Space Escape Grunge Sign, created by Nicolas Raymond and available from: www.freestock.ca